The conventional LaTeX command for typesetting partial derivative is \partial command which displays the generic partial derivative notation ∂.

\documentclass{article}

\begin{document}

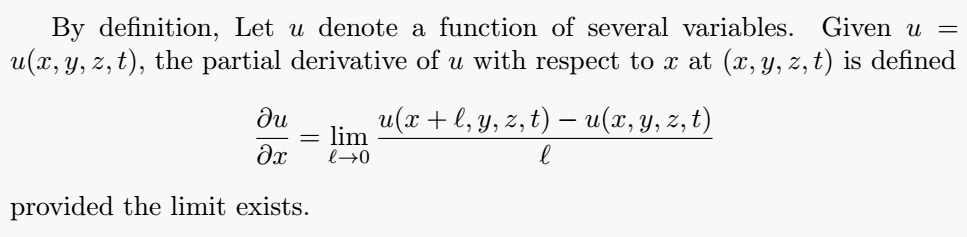

By definition, Let $ u $ denote a function of several variables. Given $ u=u(x,y,z,t) $, the partial derivative of $ u $ with respect to $ x $ at $ (x,y,z,t) $ is defined

\[ \frac{\partial{u}}{\partial{x}} = \lim_{\ell \to 0}\frac{u(x + \ell, y, z, t) - u(x,y,z,t)}{\ell} \]

provided the limit exists.

\end{document}Output :

Conventionally, partial derivatives can also be denoted using subscript notation(popular) and using some other notations.

Below are the different notations for presenting the partial derivative of a function f(x, y, z,⋯) with respect to x

| Notation | LaTeX command |

|---|---|

f’_{x} |

|

\partial_{x}f |

|

D_{x}f |

|

D_{1}f |

|

\frac{\partial}{\partial{x}}f |

|

\frac{\partial{f}}{\partial{x}} |

ux if function is defined in terms of u. Below is a demonstration of how these notations are used.

Notations and their use in LaTeX

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{amsmath}

\begin{document}

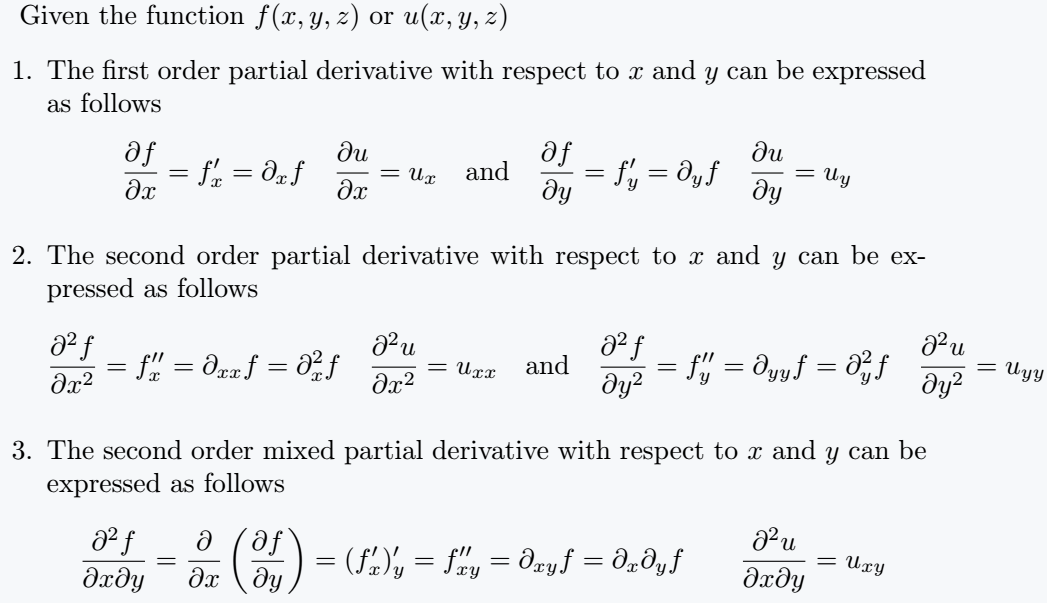

Given the function $f(x,y,z)$ or $u(x,y,z)$

\begin{enumerate}

\item The first order partial derivative with respect to $x$ and $y$ can be expressed as follows

\[ \frac{\partial{f}}{\partial{x}} = f'_x = \partial_{x}f \quad \frac{\partial{u}}{\partial{x}} = u_x \quad \text{and}\quad \frac{\partial{f}}{\partial{y}} = f'_y = \partial_{y}f \quad \frac{\partial{u}}{\partial{y}} = u_y \]

\item The second order partial derivative with respect to $x$ and $y$ can be expressed as follows

\[ \frac{\partial^2{f}}{\partial{x^2}} = f''_x = \partial_{xx}f = \partial_{x}^2f \quad \frac{\partial^2{u}}{\partial{x^2}} = u_{xx}\quad \text{and}\quad \frac{\partial^2{f}}{\partial{y^2}} = f''_y = \partial_{yy}f = \partial_{y}^2f \quad \frac{\partial^2{u}}{\partial{y^2}} = u_{yy} \]

\item The second order mixed partial derivative with respect to $x$ and $y$ can be expressed as follows

\[ \frac{\partial^2{f}}{\partial{x}\partial{y}} = \frac{\partial}{\partial{x}}\left(\frac{\partial{f}}{\partial{y}}\right)= (f'_x)'_y =f''_{xy} = \partial_{xy}f = \partial_{x}\partial_{y}f \qquad \frac{\partial^2{u}}{\partial{x}\partial{y}} = u_{xy}\; \]

\end{enumerate}

\end{document}Output :

Examples

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{amsmath}

\begin{document}

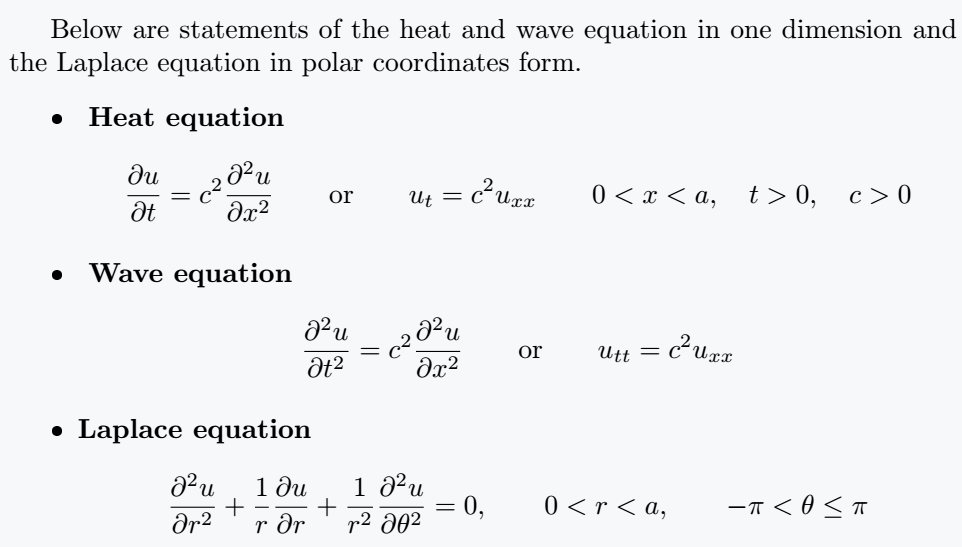

Below are statements of the heat and wave equation in one dimension and the Laplace equation in polar coordinates form.

\begin{itemize}

\item\textbf{ Heat equation }

\[ \frac{\partial{u}}{\partial{t}} = c^2\frac{\partial^2{u}}{\partial{x^2}}\qquad \text{or} \qquad u_t = c^2u_{xx}\qquad 0 < x < a, \quad t > 0, \quad c>0 \]

\item\textbf{ Wave equation }

\[ \frac{\partial^2{u}}{\partial{t^2}} = c^2\frac{\partial^2{u}}{\partial{x^2}} \qquad \text{or} \qquad u_{tt} = c^2u_{xx} \]

\item \textbf{Laplace equation}

\[ \frac{\partial^2{u}}{\partial{r^2}} + \frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial{u}}{\partial{r}} + \frac{1}{r^2} \frac{\partial^2{u}}{\partial{\theta^2}} = 0, \qquad 0 < r < a, \qquad - \pi < \theta \leq \pi \]

\end{itemize}

\end{document}Output :

Hessian Matrix

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{amsmath,amssymb}

\begin{document}

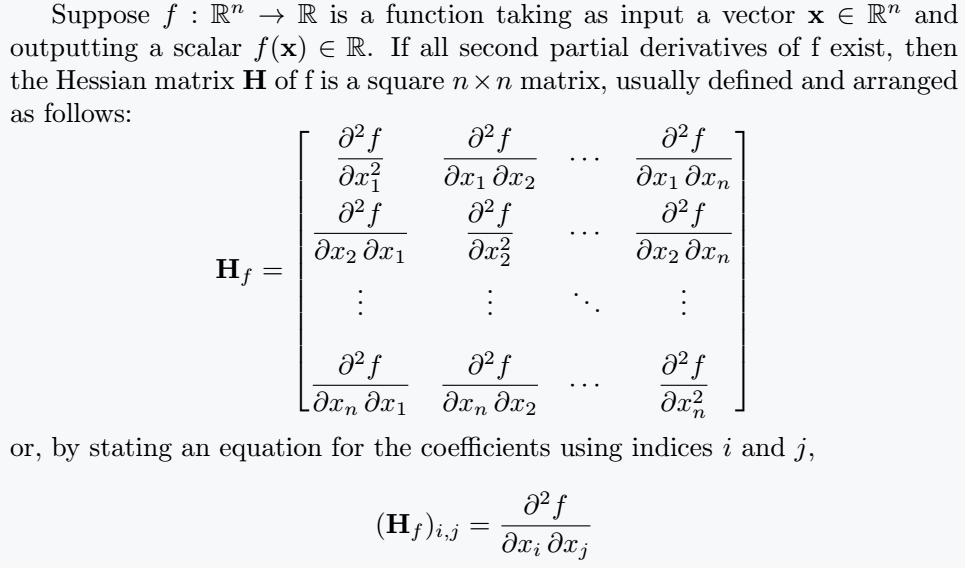

Suppose $ f:\mathbb{R} ^{n}\to \mathbb{R} $ is a function taking as input a vector $ \mathbf{x} \in \mathbb {R} ^{n} $ and outputting a scalar $ f(\mathbf {x} )\in \mathbb{R} $. If all second partial derivatives of f exist, then the Hessian matrix $ \mathbf{H} $ of f is a square $ n \times n $ matrix, usually defined and arranged as follows:

\[ \mathbf {H} _{f}= \begin{bmatrix}

\dfrac{\partial^{2}f}{\partial x_{1}^{2}} &\dfrac {\partial^{2}f}{\partial x_{1}\,\partial x_{2}}& \cdots &\dfrac{\partial ^{2}f}{\partial x_{1}\,\partial x_{n}}\\[2ex]

\dfrac{\partial^{2}f}{\partial x_{2}\,\partial x_{1}}&\dfrac{\partial^{2}f}{\partial x_{2}^{2}}&\cdots &\dfrac{\partial^{2}f}{\partial x_{2}\,\partial x_{n}}\\[2ex]

\vdots &\vdots &\ddots &\vdots \\[2.2ex]

\dfrac{\partial^{2}f}{\partial x_{n}\,\partial x_{1}}&\dfrac{\partial ^{2}f}{\partial x_{n}\,\partial x_{2}}&\cdots &\dfrac{\partial^{2}f}{\partial x_{n}^{2}}

\end{bmatrix} \]

or, by stating an equation for the coefficients using indices $ i $ and $ j $,

\[ (\mathbf{H} _{f})_{i,j}={\frac {\partial^{2}f}{\partial{ x_{i}}\,\partial x_{j}}} \]

\end{document}Output :

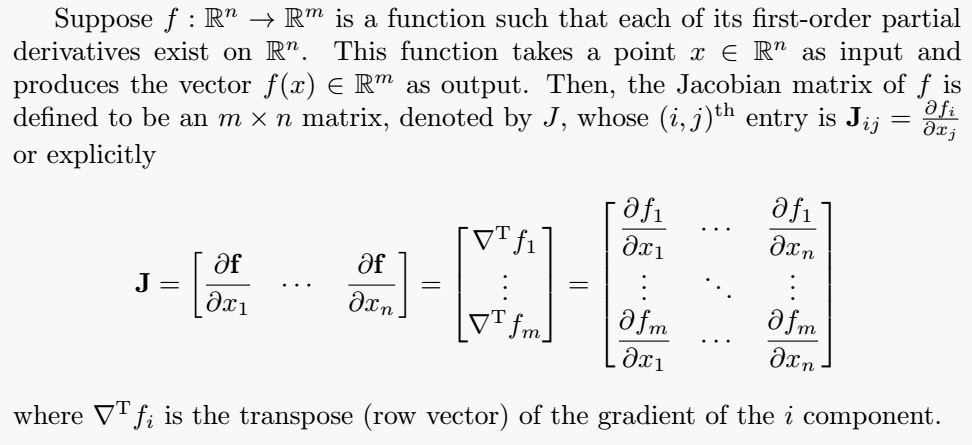

Jacobian Matrix

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{amsmath,amssymb}

\begin{document}

Suppose $ f : \mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbb{R}^m $ is a function such that each of its first-order partial derivatives exist on $ \mathbb{R}^n $. This function takes a point $ x \in \mathbb{R}^n $ as input and produces the vector $ f(x) \in \mathbb{R}^m $ as output. Then, the Jacobian matrix of $ f $ is defined to be an $ m \times n $ matrix, denoted by $ J $, whose $ (i,j)^{\text{th}} $ entry is

$ \mathbf{J} _{ij}=\frac {\partial f_{i}}{\partial x_{j}} $ or explicitly

\[ \mathbf {J} = \begin{bmatrix}

\dfrac{\partial \mathbf {f} }{\partial x_{1}} & \cdots & \dfrac {\partial \mathbf{f}}{\partial x_{n}}

\end{bmatrix} = {\begin{bmatrix}

\nabla^{\mathrm {T} }f_{1}\\

\vdots \\

\nabla^{\mathrm {T} }f_{m}

\end{bmatrix}}

=\begin{bmatrix}

\dfrac {\partial f_{1}}{\partial x_{1}} & \cdots & \dfrac {\partial f_{1}}{\partial x_{n}}\\

\vdots &\ddots &\vdots \\

\dfrac {\partial f_{m}}{\partial x_{1}} &\cdots &\dfrac{\partial f_{m}}{\partial x_{n}}

\end{bmatrix}\]

where $ \nabla ^{\mathrm {T} }f_{i} $ is the transpose (row vector) of the gradient of the $ i $ component.

\end{document}Output :

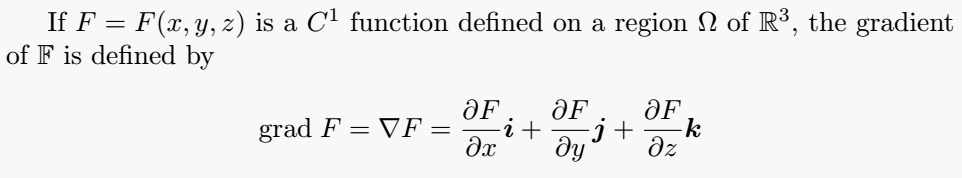

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{amsmath,amssymb}

\begin{document}

If $ F = F(x,y,z) $ is a $ C^1 $ function defined on a region $ \Omega $ of $ \mathbb{R}^3 $, the gradient of $ \mathbb{F} $ is defined by

\[ \text{grad}\; F = \nabla{F} = \frac{\partial F}{\partial x}\boldsymbol{i} + \frac{\partial F}{\partial y}\boldsymbol{j} + \frac{\partial F}{\partial z}\boldsymbol{k} \]

\end{document}Output :

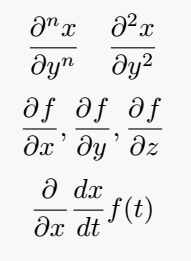

Use newcommand and physics package

Newcommand is used to convert a large syntax into a smaller syntax. This method is effective instead of writing large syntax to represent the same expression over and over again.

\documentclass{article}

\newcommand{\pdvx}[3][]{\frac{\partial^{#1} #2}{\partial {#3}^{#1}}}

\begin{document}

\[ \pdvx[n]{x}{y}\quad\pdvx[2]{x}{y} \]

\[ \pdvx{f}{x},\pdvx{f}{y},\pdvx{f}{z} \]

\[ \pdvx{}{x}\frac{dx}{dt}f(t) \]

\end{document}Output :

An optional argument is used with the \pdvx[opt arg]{arg}{arg} command that represents the power of the partial derivative.

Macro that has been created for convenience is defined in the Already Physics package as \pdv.

So, if you look at some of its uses below, you will understand why it is beneficial to write short commands instead of writing large syntax.

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{physics}

\begin{document}

\[ \pdv{x}{y}\quad\pdv{f}{x} \]

\[ \pdv[n]{f}{x}\quad \pdv[3]{f}{x} \]

\[ \pdv{x}(\frac{dx}{dy}) \]

\[ \pdv{f}{x}{y}\quad\pdv*{f}{x} \]

\end{document}Output :

Conclusion

This article gives you full coverage of how to typeset partial derivatives using the \partial command and a few other methods that we have seen.

A good mastery of this tutorial will improve your mathematical typesetting, especially in the domain of partial derivatives, partial differential equations, and other concepts in higher mathematics that make use of it.